Ward 1 teacher "creating citizen scientists" one class debate at a time

How Banneker High Environmental Science teacher Dr. Wendy Woods is localizing her curriculum to create not only well-rounded students but environmentalists.

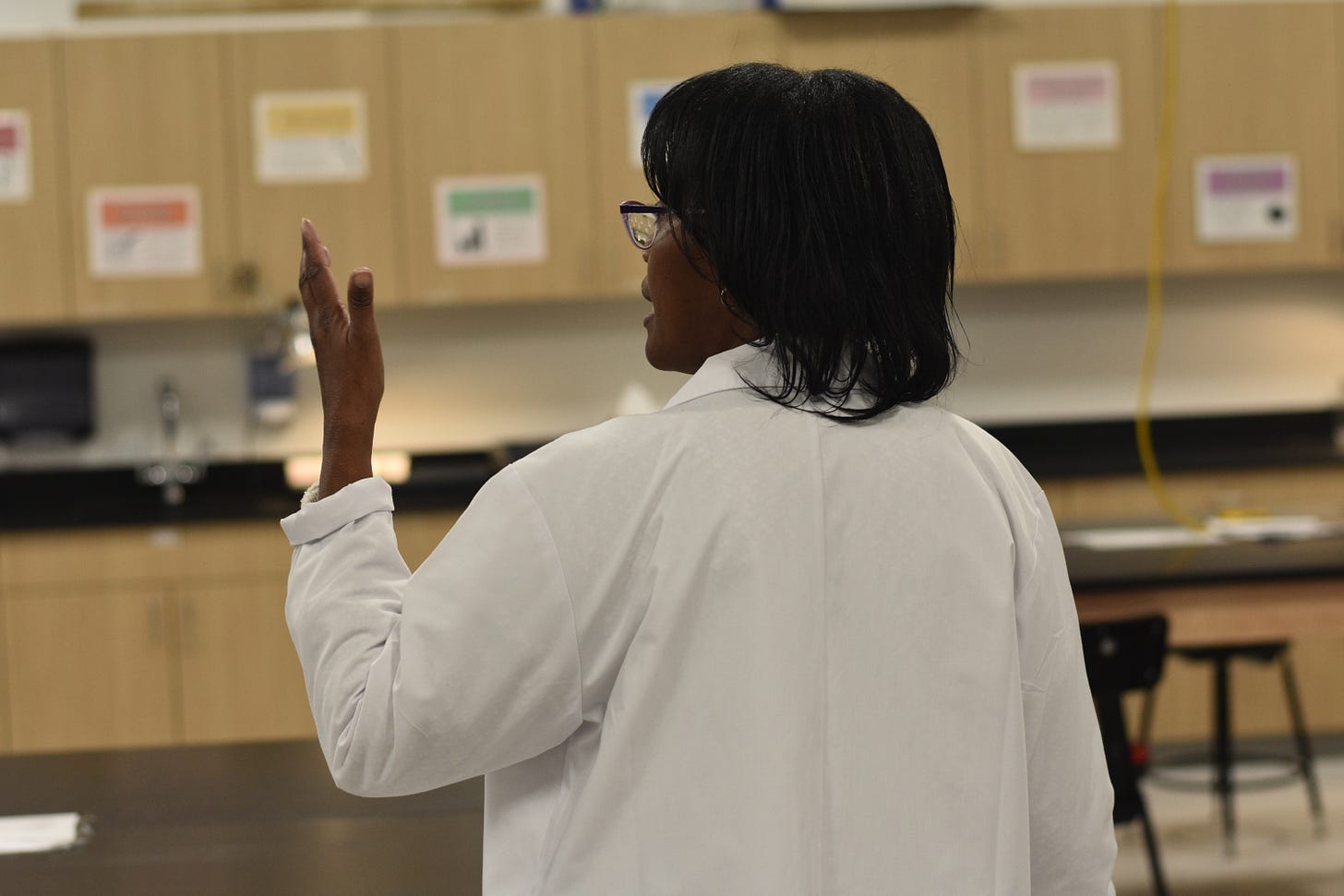

Dr. Wendy Woods witnessed three of her students argue with each other in front of the entire class. And she was proud.

The kids threatened to send their fellow classmates to prison or fine them hundreds of thousands of dollars. They had exceeded her expectations. She smirked as she took notes and challenged them with follow up questions, recognizing how much they committed to their roles.

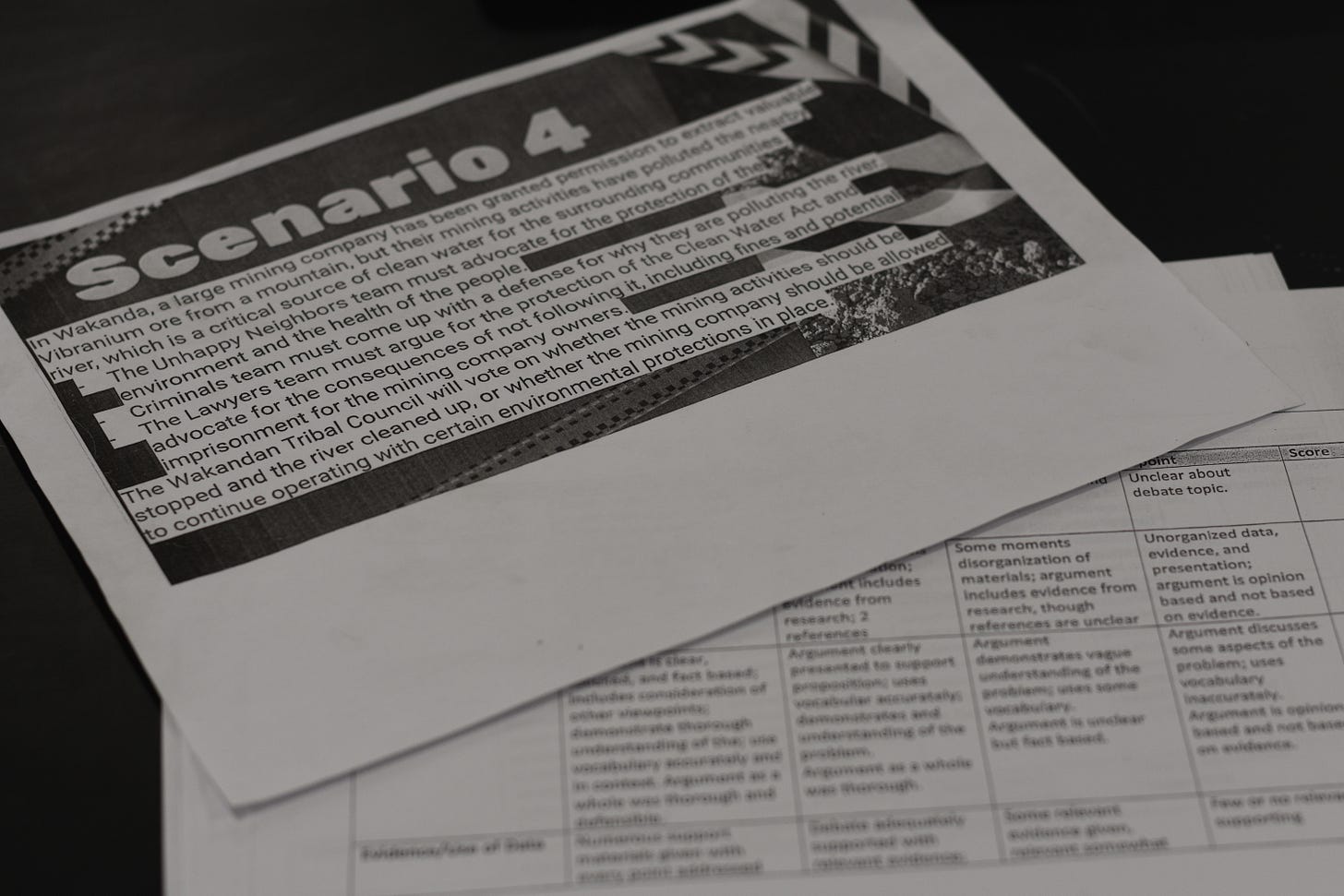

Woods had assigned her Environmental Science students at Banneker High School in Ward 1 to debate violations of environmental protection legislation in groups as “the unhappy neighbors,” “criminals,” and “lawyers.”

The students were assigned fictitious scenarios and legitimate regulations to research and debate – a mining company in Wakanda who extracted vibranium ore and released pollutants in the water, a dark arts wizarding academy planning to build their new school in protected lands.

“The law that was violated with the mining of the vibranium was the Clean Water Act,” scenario four’s “lawyer” said in his presentation Nov. 21. “Miners violated this act. Their mining caused a lot of pollution in the water and made unhealthy and unsafe to the aquatic life living there. Due to these facts, I believe the mining corporation should be shut down and the workers be put on trial.”

The students watching the presentation quietly “ooh-ed” and looked around the room. The “criminal” was up next.

“Mining the vibranium could lead to the future success of the country,” the scenario four “criminal” said. “It is not an act of selfishness, however an act of indifference. We understand that the water is being polluted. However, this is a miniscule amount of pollution compared to larger countries such as China.”

They came up with elaborate and nuanced arguments, referencing the Clean Water and Air Acts as well as the Endangered Species Act. The “criminals,” dedicated to their position, used the necessity for more low-income housing to be developed on protected lands and economic prosperity for their small village as rational for their position.

The “unhappy neighbors'' raised complaints about health issues like respiratory cancer in loved ones and the desire to protect the endangered species in their communities. The lawyers brought charges on the “criminal” based on real laws and regulations and issued recommendations to “the council” – the class – on what the punishments should be based on the real-world consequences of their violations.

“When we talk about those issues, that environmental racism, the approach is to give projects, and then do similar scenarios like what you all saw modeled here, town halls,” Woods said. “This particular instructional strategy seems to be very favorable because you get into that debate. And it pushes students to kind of like deep, dig deep, and you just relate on some level to yourself, because you're trying to defend your position.”

This is Woods’s first year teaching at Banneker High School after several years of teaching in Ward 8 of Washington. Banneker has a 96.3% minority enrollment rate, with 71.1% of students being Black, according to US News. Prior to teaching, she was a practicing Doctor of Podiatric Medicine with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in biology, chemistry and education.

But she started her education in the same place she teaches now.

She was one of the few students in the inaugural class at Banneker, starting as a freshman when the school opened and is now giving back to her community.

“I get to pour back into the students here what was poured into me while I was here,” she said. “One of the first things that students here asked was, ‘you're an alum of the school, you get us.’ And I understand what that means.”

Despite her first career being in medicine, she teaches Environmental Science to 85 seniors and designs her own curriculum intertwining law, heath and the liberal arts into science.

“Everybody's thinking environmental science is… just like a filler elective,” she said. “It is one that encompasses all of the other sciences, you have a biology component, you have a chemistry component, you possibly have physics as we saw a student demonstrating Newton's law, but environmental issues impact every one. You are a contributor to it, whether you acknowledge it or not. And then you're also a person that can be a part of the solution. So the first thing is being able to acknowledge what those issues are. And that's the first step to be able to look at solutions, because what is happening impacts us as a whole.”

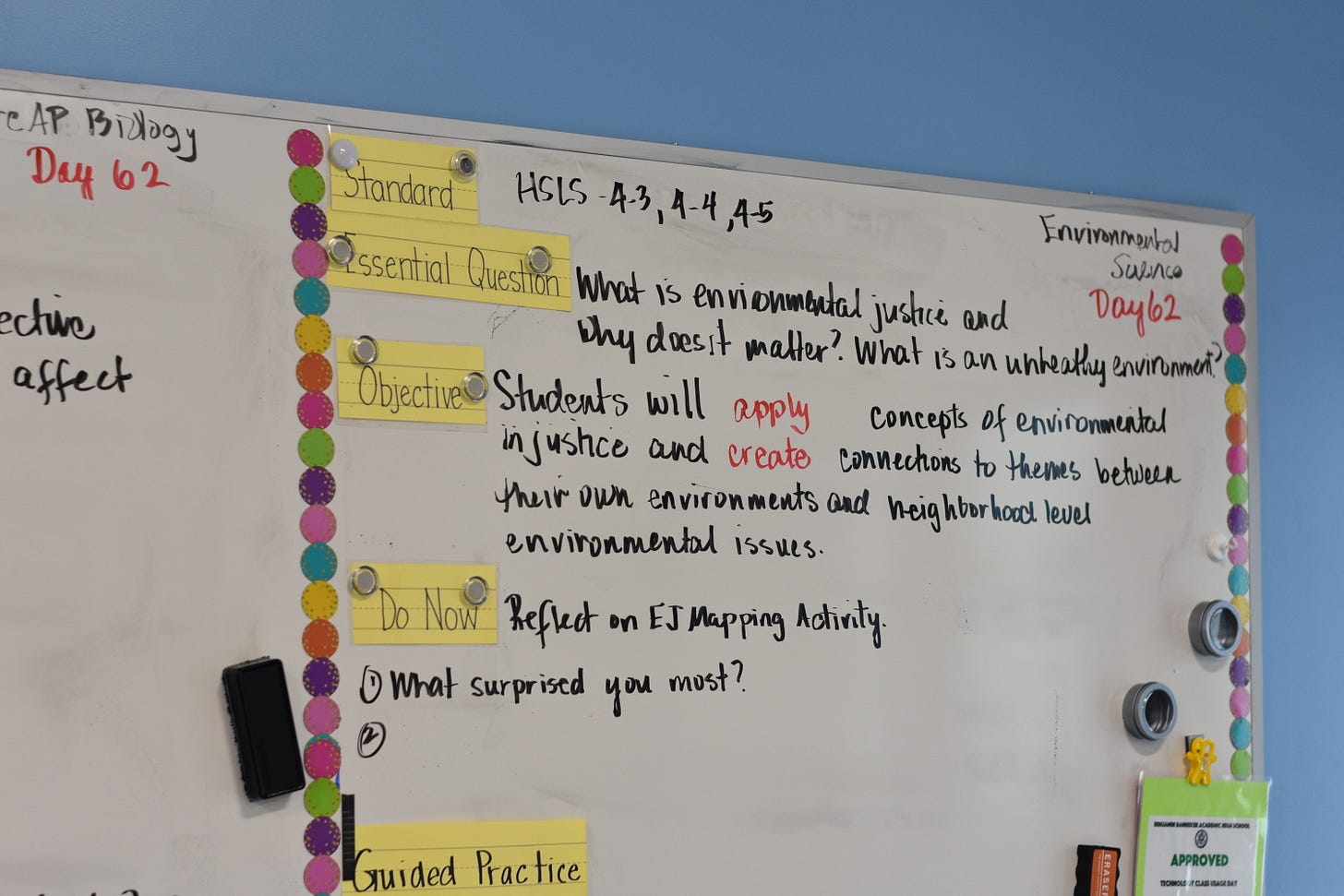

This town hall assignment the students participated in was the first lesson in a “mini-unit” Woods created to cover environmental justice and racism. The start of two weeks of identifying what environmental issues already exist in the students’ own communities and what are the solutions to them. Two weeks of defining the terms “equality,” “equity” and “liberation” as it relates to their own environment.

Students need to see the relevance of it. And then that's what piques the interest. And from there, you become the advocate, because everybody's an advocate for environmental issues in our community. We're all advocates, and it changes your perspective.

-Dr. Wendy Woods

As Woods progresses through the year, covering units of air, land and water, she plans on integrating the ideas and the approach to environmental justice learned in this unit to instill a pattern of thinking in the students to see how this pertains to their lives.

“[Environmental racism] is not isolated. So you feed it into each of the topics,” she said. “So the students need to see the relevance of it. And then that's what piques the interest. And from there, you become the advocate, because everybody's an advocate for environmental issues in our community. We're all advocates, and it changes your perspective.”

Her approach is starkly different from the standardized curriculums in Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB) Environmental Science classes, she said.

“I do have autonomy over the curriculum,” Woods said. “It's very generalized for AP, it is kind of taught in components… Whereas in this approach, I get to merge in a different point. So I can merge in environmental justice right into where I want it to go and link it to every unit, because that's a case study, right? And then you get to show relevance to modern day.”

AP Environmental Science has nine standard units that cover the same information in Woods’s class like water and air pollution, biodiversity and environmental regulation, according to the College Board. However, the standardized curriculum has no fixed place for a unit on environmental justice or racism, like Woods has implemented and woven through each other unit of Land, Water and Air.

Caleb Jenkins-Hall had never learned about environmental justice or the effects on climate change in his community in other science classes before taking Woods’s class now as a senior.

“Something that stood out to me was how blatant the environmental injustice that was in the impoverished areas of minority communities,” Jenkins-Hall said. “It was very obvious that those communities had a disadvantage when it came to having a safe environment. And also, another thing that stood out to me was the lack of attention that it was getting from government officials.”

Senior Edward Laura never realized how much hazardous waste was released in his neighborhood in Northwest Washington until working on an Environmental Justice mapping assignment in Woods’s class Dec. 4, he said.

The assignment required the students to use the Environmental Protection Agency’s EJ Screen online mapper to identify key pollutants and injustices in their neighborhoods and surrounding Banneker High School.

“I didn't realize was how much like as hazardous waste goes throughout all of DC, especially like in my neighborhood. I live in Northwest, but it's like, far off,” Laura said. The people in his community are “definitely not aware because unless you actually intend on studying this subject. You probably won't even realize the types of things that are going on in your community unless you look for them. And most of the time, we're not looking for them.”

This assignment was eye-opening for senior George Goicochea as well — looking into the environmental disparities in Ward 7 and 8 compared to the more affluent areas of Washington, he said.

“At first, when you're thinking of environmental justice, you're really thinking about, like, how is it that we as a human race are impacting the world around us, but I mean, when you take a deeper look at it, we are not only affecting the environment, but ourselves as well,” Goicochea said. “There's a disparity between who is being impacted the worst. There are definitely groups of people, minorities, especially who face the brunt of the bad impacts, while other people can afford to just ignore things like that.”

Her approach to teaching students about the environment is unique and evolving as she develops the curriculum in this first year at Banneker. Each lesson, each debate she tries to bring back to the kids and their personal situations.

After the students finished presenting their debates, Woods asked the class “Why are environmental laws important to your own communities?”

“Our bodies of water are green,” Kidus Yohannes, senior, said, pointing out issues he has seen in his neighborhood.

“I’d rather not know where my water coming from,” another student said, lifting up her empty bottle of water. “Please don’t ruin water for me,” she laughed.

When another class period was discussing illegal fishing in the Anacostia River, senior Janiya Drayton, who lives near the river, questioned the practice.

“That’s an okay idea, but like who’s going to monitor that,” Drayton said. “Who’s going to monitor how many fish people are taking out of the Anacostia River? It’s not like they can eat them, and the police are needed elsewhere, especially in a minority community.”

The class discussed housing and water quality – every single student in the class said they don’t drink water out of the tap and only consume bottled water. They talked about crime and air quality. Health disparities and asthma.

“You hear the children talk about deforestation a lot, because they definitely understand that part of the concept and what that has done. And then they understand how that impacts our environment? The first thing they will tell you is like, we don't have a lot of trees,” Woods said. “But just to hear that connection, is really important. They do connect back to our global warming and climate change. And it's kinda like the goal… So when we get to that unit, I don't have to teach the unit, we just kind of bridge everything together, explain what's happening.”

Woods also facilitates the Health Science Club on campus which was co-founded by one of her environmental studies students and senior Courtney Howard.

Howard lives in Southeast Washington but is graduating from Banneker in the Spring. She is currently applying to colleges to pursue a biology degree to eventually become a cardiovascular perfusionist which monitors the heart and lungs during surgery and make sure they are stable, she said.

The club helps other high school students learn about the possible careers in medicine they can pursue and what might suit them best.

“I joined Model United Nations when the COVID pandemic happened, a lot of the conferences switched [committees] from women's rights and labor laws to getting medicine to underdeveloped countries,” Howard said. “I really took a liking to that because I live in Southeast DC and from looking at the different characteristics of people in undeveloped countries that are working on their medicines, I saw some similarities in my own community.”

She recognized the health care disparities that exist in her community and wants to pursue medicine to close the gap on the amount of black health care practitioners there are and how black people are treated as patients in medicine.

While her number one priority is applying to colleges and pursuing a career in medicine, she has seen the adverse effects of climate change in her community from the extreme heat the past few months in Washington and the air pollution in her neighborhood, she said. She knows health effects from climate effects will reveal themselves in her future career.

“Climate change and pollution creates asthma, and it also causes a lot of negative effects to the body,” Howard said. “And so when I am taking patients, that's something I would have to think about regarding a patient’s health like their asthma, maybe a heart defect, things like that.”

After Woods’s class on environmental justice and racism, the questions on “equity,” “equality” and “liberation” struck a chord with Howard.

“We made this [club] so we can shed light on different things going on in our neighborhoods like I was very passionate about Southeast DC and how the hospital [DC General] closed and how this affected generations of people not getting good healthcare,” she said. “And we let other people talk about, you know, what they're experiencing in their neighborhood.”

But the words “climate change” aren’t always met with enthusiasm in minority or lower income communities, Dr. Amy Yeboah Quarkume of Howard University said.

She is an associate professor of Africana Studies and Data Science and is affiliated with the Environmental Studies department at Howard. Quarkume also is leading research on environmental data bias in underrepresented communities.

“Some of the most pressing issues are income, crime, employment,” Quarkume said. “But if you ask individuals, do they prioritize their children having a safe, clean, healthy space? Those are our climate issues. So it's just a sense of language, right? So do an African-American and minority communities prioritize climate as they do? They just articulate it differently than a researcher may be looking for. The sense that people want clean air, clean water, they want living conditions that are healthy. That's definitely what we see them prioritizing.”

In a 2020 study done by Third Way, qualitative research found that Black Americans shoulder an “unequal burden” to “environmental degradation.” Despite this, the study reports that while Black Americans do care about climate change, it is not a number one priority and tend to be “left out” of conversations about their environment.

“Participants said no one is talking specifically to them about climate change or the environment,” the report states. “Multiple participants said that when they hear people address climate change, the people say things like “it affects us all” or speak in terms of global climate change. Still others said they only hear it addressed when election season comes around, as a talking point.”

Hyper-localized communication and education are part of the solution, Quarkume said.

“I've lost hope in my parents learning how to recycle,” Quarkume said. “I think if you start with young people and get them excited about knowing what they have, knowing what they can control, knowing what they can create, to be able to make change, that is where we see the biggest gains.”

Her research focuses on what information about their environment lower income and minority communities receive and how accurate it is. These communities lack localized information about why their children are developing asthma on a higher level or why their air smells funny, she said.

“I think from an educator's standpoint, we're not transparent about what they can do here. And what are some of the ways in which, even in your backyard, you can test your own water, you can get a monopod monitor your own air quality?” Quarkume said. “We should start earlier… trying to create citizen scientists at a younger age, and not just engage high school or undergrad students.”

This is one of Woods’s goals in creating the curriculum for this course at Banneker.

“If I construct a learning task for students where they can see the relevance of the course to their day to day life, you get the engagement, students are intrigued,” Woods said. “They now are equipped to manage and apply what they have learned to their daily lives. And ultimately, you're an environmentalist, whether you acknowledge it or not.”

One of the presentations for the town hall assignment, a student mentioned a loved one who suffered from lung cancer as an argument for one of the air pollution case. This was something Woods did not expect but realized how important it was, she said.

They see the inequities that are occurring. And then my question to them is, what are you going to do about it?

-Dr. Wendy Woods

She sees each and every day that her students are becoming more engaged as they see how their environment and daily lives are impacted by climate change. They ask her questions about her time as a medical practitioner and about the health disparities they see. They ask her about why they can’t just leave some trees in their neighborhoods. They ask her why it is still 70 degrees Fahrenheit in October.

“It's important for high school students to see the relevancy of the courses that they're studying, to their day to day… When you invest it, your approach is different. And it's favorable. Your conversation matters more,” Woods said. “They see the inequities that are occurring. And then my question to them is, what are you going to do about it?”